The death of a newsman — and an addiction.

After smoking silenced Peter Jennings, another reporter faces facts. It was over a year ago, on Aug. 7, 2006 that Peter Jennings died of lung cancer. I reported a story on NBC Nightly News about the death of the famed ABC News anchor, my assignment a review of the links between smoking and lung cancer. Peter’s death struck me as it did millions of others, a giant figure of journalism silenced so suddenly; but I also felt the loss personally because I’d had the privilege of being his colleague for awhile, when we both worked out of ABC’s London Bureau three decades earlier.

A smoker myself, I went home after that night’s broadcast with six cigarettes left in the pack in my briefcase. The next day Dana Reeve, the widow of the actor Christopher Reeve and a non-smoker, revealed that she too had been diagnosed with lung cancer, and I reported that story as well.

But a thought had taken hold in me and turned into a vow: I went home and announced to my old dog who sat next to me on the couch (my wife was overseas) that the cigarette I was about to smoke, the remaining one of those six in the pack, would be it. No more. Finished. I lit up, took a half-dozen deliberate drags over the next few minutes, stubbed it out and watched the last wisp of smoke disappear. I said to the dog, “Done!” So far, since then, that remains true.

I’d smoked for four decades, since I was a young teenager. In the early years I’d stop during basketball and baseball seasons but from my late college years on, once I’d landed irreversibly in a reporter’s life, I rarely went a single day without cigarettes.

For a few months in the spring and summer of 1974 I did cut way back from my pack-a-day habit, and even had a few of those totally smoke-free days. But the Watergate drama was building to its crescendo then, I was covering it, and I was in Washington to watch Nixon’s resignation the night of Aug. 8 with the Massachusetts Senator Edward Brooke who, after it was over and after I’d filed my report, handed me one of his Benson & Hedges 100s. There were no more smoke-free days, until Peter died.

And when he did, and when it was lung cancer that took him, I was shocked and embarrassed as I read through the research to see how much I didn’t know or had declined to note about the link between cigarette smoking and the deadliest of cancers. I’m a reasonably smart guy, I thought, as I processed one grim fact after another, so how could I have not known the basic statistics — for example, that 90 percent of male lung cancer patients are or were cigarette smokers. Or that smokers are up to 20 times more likely to develop lung cancer (20 times!) than are non-smokers and die an average of 14 years sooner. Or that by the time you have the symptoms Peter had when he was diagnosed — the shortness of breath, raspy cough and sudden weight loss — it's probably too late.

And how was it that I’d decided to include a chest X-ray with my annual physical, to have a better chance at early detection and thus early treatment, I thought, a way to keep smoking until I had to quit, when a chest X-ray and even a conventional CAT scan don’t effectively screen for lung cancer?

I’d never asked the right questions about smoking and lung cancer. I’d never really wanted the answers.

Instead, I’d kept it to a pack a day and remained alert for those occasional stories about the 90-year-old codger who attributed his fine fettle to the cigarettes and whisky he continued to consume daily. And anyway, I was satisfied for years to seem to be living by the credo often attached to stories about the late James Dean: “Live fast, die young, leave a nice looking corpse.”

What I did recite, often without prompting as I moved into middle age, was the blunt view that my life had long been full and laced with more luck and blessings than I’d earned, and that if I was hit by that proverbial bus the next day, life would owe me nothing. Sure, I’d taken some steps to take better care of myself: that annual physical, quitting drinking many years ago, paying more attention to diet and exercise. But that was because I still wanted to be able to play a couple of hard sets of tennis, or handle my boat in heavy weather, or continue to report effectively from war zones or other physically demanding assignments. I’d laugh when people bugged me about my smoking: “Hey, it’s my last vice! I enjoy it!” I did. It was. Until the day Peter Jennings died.

In the weeks after I quit, my friends, family and colleagues rallied around me, and I was touched. I’d get these e-mails saying “Call me!” if I had an urge to light up. Once, rushing into my office on deadline, I found a package on my desk with a card taped to it: “Thought I’d buy you the next few rounds.” It was from a colleague, a two-month supply of quit-smoking patches.

It turned out I didn’t need them. I was done smoking, though I’d really just begun to think about it. And about how the relatively paltry funding for lung cancer research suffers from the impact of smoker’s guilt — the "we bring it on ourselves" lament that even Peter referenced in his very last broadcast, saying he’d “been weak” and had gone back to smoking after 9/11. Less than 1/10th of the research dollars spent on breast cancer are spent on lung cancer per death, for example. I thought about how there’ve been few celebrity-led commercial campaigns for lung-cancer research — because so few lung cancer patients, only about 15 percent, have a five-year survival rate or ever get healthy enough again to lead the fund-raising charge or the next 5K run.

So 160,000 Americans died of lung cancer last year, at least as many will be newly diagnosed this year, and unless its next victim is a Peter Jennings or Dana Reeve — who would also be taken by the disease — it remains a largely invisible mass killer whose opponents have no champion or spokesperson, and whose cures and treatments seem as distant or feeble as ever.

A few months ago a longtime acquaintance of mine asked me how I’d finally been able to kick the habit. I said I didn’t know, that maybe it was just my time to quit. Or, maybe, that I’d just been frightened into quitting by what had happened to the man I’d worked with (and smoked with) all those years ago: diagnosis to death in a mere four months. Then I said something I’d never said before, words I’d never spoken to anyone: “I guess what’s different is that now I want to live as long as I can. There are stories I want to cover or at least see how they turn out. More things I want to write, places I want to travel to. I want to sail some more, get better at golf, enjoy my marriage and continue being a father. Forget about getting hit by that bus: I want to live.”

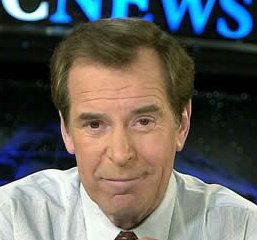

Mike Taibbi is an NBC News correspondent.

© 2006 MSNBC Interactive